Heni Unwin: Māori scientist making waves in the realm of Tangaroa

17 November 2021 | Read time: 7 minutes

We sit down with Heni Unwin, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairoa, Rongomaiwahine, Ngāi Tūhoe, Te Atihaunui-a-Papaarangi, and talk about what makes her tick and her advice for rangatahi looking at science as a career pathway.

It was on a trip to Rarotonga as a youngster, snorkelling in the sparkling waters where our tupuna once lived, Heni Unwin became fascinated with the underwater world of Tangaroa (Māori God of the sea). Returning to Aotearoa she knew she wanted to become a marine scientist and is currently undertaking study towards a Masters degree in Environmental Science. She said:

“I’m studying a masters because I want to be the best scientist I can for the Māori communities I serve. This qualification is not just about furthering my career and ensuring that I can get future funding, it's actually to secure funding for those Māori communities I most want to work for.”

Mātauranga Māori: the foundation of a career in science

Born to a Pākeha mother and a Māori father, she has been inspired by her parents who made sure Heni and her brother knew their taha Māori. This cultural grounding has become the foundation of her career in science where she says it's not easy being Māori, she explained:

“As for many Māori in their occupation, we are in culturally unsafe environments, even now returning to university; I thought it might have changed over the years but these institutions still don’t provide for Māori students. I am the only Māori in my classes, except for one class out of eight, and that one is really great – there are three Māori in there including myself. Otherwise it makes being in class difficult because I'm always coming from an indigenous perspective and it has made me an outlier and at some points even a lecturer for Māori culture.”

Heni has been employed by the Cawthron Institute for almost three years as a researcher and has worked on both the Sustainable Seas and Science for Technological Innovation (SfTI) National Science Challenges (NSC). She said:

“I wouldn't be in my role if it wasn’t for the National Science Challenges. The NSCs provided a platform for more Māori to be included in the science sector through the Vision Mātauranga policy. This policy also has really brought to light the inequity of Māori in the science sector but also the amount of researchers who cannot do kaupapa Māori research that benefits Māori communities.”

With SfTI’s support, Heni is also working closely with FoMA Innovation to build relationships between the research sector and Māori enterprises to help identify projects that could have mutual benefit for Māori and the science community.

Measuring mussel gaping with maramataka and sensors

Heni’s role on the Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge has ended. However, she continues to work on the SfTI Precision Aquaculture Spearhead project as a researcher and Vision Mātauranga (VM) lead. She hopes her latest project can help Māori transform the aquaculture sector.

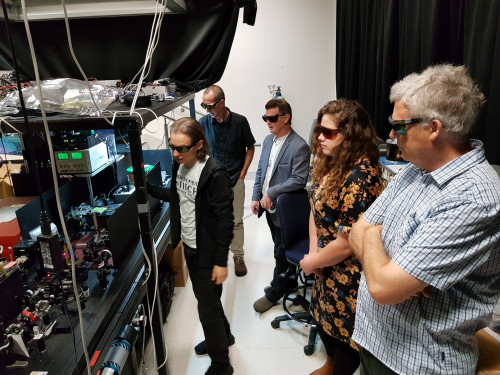

The core of the project is developing remote technology to monitor aquaculture farms in the marine environment. The project is developing technology: imaging sensors, sea-to-land communication links and data analytics.

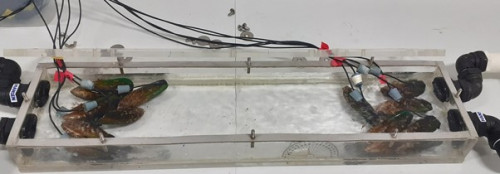

Heni has been working on the mussel gaping behaviour and analysing the data. She explained, “Mussel gaping is when the mussels open and close. They are usually open 80-90% of the time, and this is when they filter through water and how they get their food and oxygen. When they detect a threat such as: pollution in the marine environment, high sedimentation, predators, or toxic algae, they shut and won’t open for a while.”

“They can act as sentinel species telling you about the environment and the ocean. It’s like they are a biological sensor talking to you saying that something is wrong in the environment. So instead of looking at the chemical properties of the water or temperatures etc, we can gather information from the animal itself. The sensors we attach to the mussels are called non-invasive sensors because they're just glued to the top with a magnet on the other end. It measures the distance and the rhythms of the mussel.”

There's also a whole other aspect of this because they also follow the rhythm phases of the moon. So you can get a maramataka (moon/lunar phases) on the mussel itself. Mussels are individuals, they gape differently to each other but when they start working together, that's when, you know, there's a problem.”

Heni plans on doing further investigations into the maramataka, researching environmental maramataka for each region in Aotearoa-NZ. She said, “Depending on where you put the sentinels because not all regions are the same, similar to how the weather is different in each region, these factors also create variable changes in the mussels.”

Collectively Interweaving Te Ao Māori with science

Heni’s passion for the taiao is evident in her commitment to her work, but she knows that she can’t do it alone. Interweaving Te Ao Māori with western science is mahi for the collective and she has advice for rangatahi that are considering science as a career pathway:

“I haven’t always had the best grades, I struggled in universities because I couldn’t always bring my Māori culture with me and I found it difficult learning about processes that I disagreed with. I was tenacious because I wanted to take care of the taiao, my whānau, hapū and iwi and this was the best way for me to do that.

"I figured out that exams and grades aren’t the true measure of your intelligence or a true representation of how you work. So, don't be discouraged if you are finding it hard and remember Māori have always been scientists, it’s reflected in our pūrakau (stories), our mātauranga, our tikanga and kawa.”

If her past work is anything to go by, Heni’s future work looks set to break boundaries and transform spaces across the undersea world of Tangaroa.

More from Heni

- Alyssa Thomas, an intern working with Heni explains how their Cawthron research draws upon mātauranga Māori to enhance understanding of Kūtai mussel health.

- Te Apārangi, The Royal Society speak with Heni Unwin & Te Rerekohu Tuterangiwhiu about their roles at Cawthron Institute as kairangahau researchers and the importance of Te Ao Māori in changing the way we interact with our environment.

- Watch Heni Unwin demonstrate a cool ocean current simulation experiment in a Cawthron video series ‘Science at Home with The Cawthron Institute’.